Mr. Leggett was trusted too soon after his operation in the fire department. --Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 22, 1877

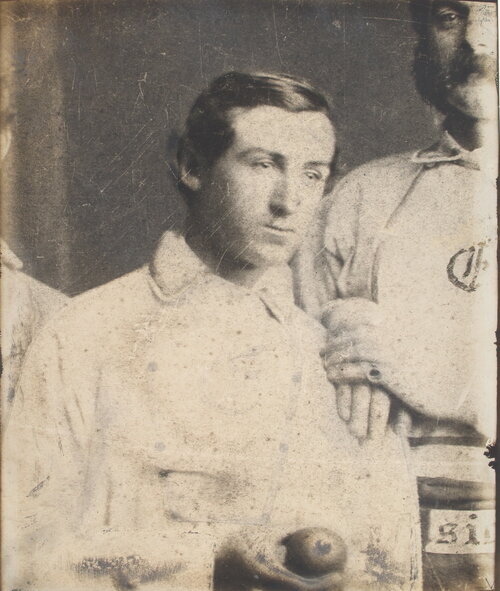

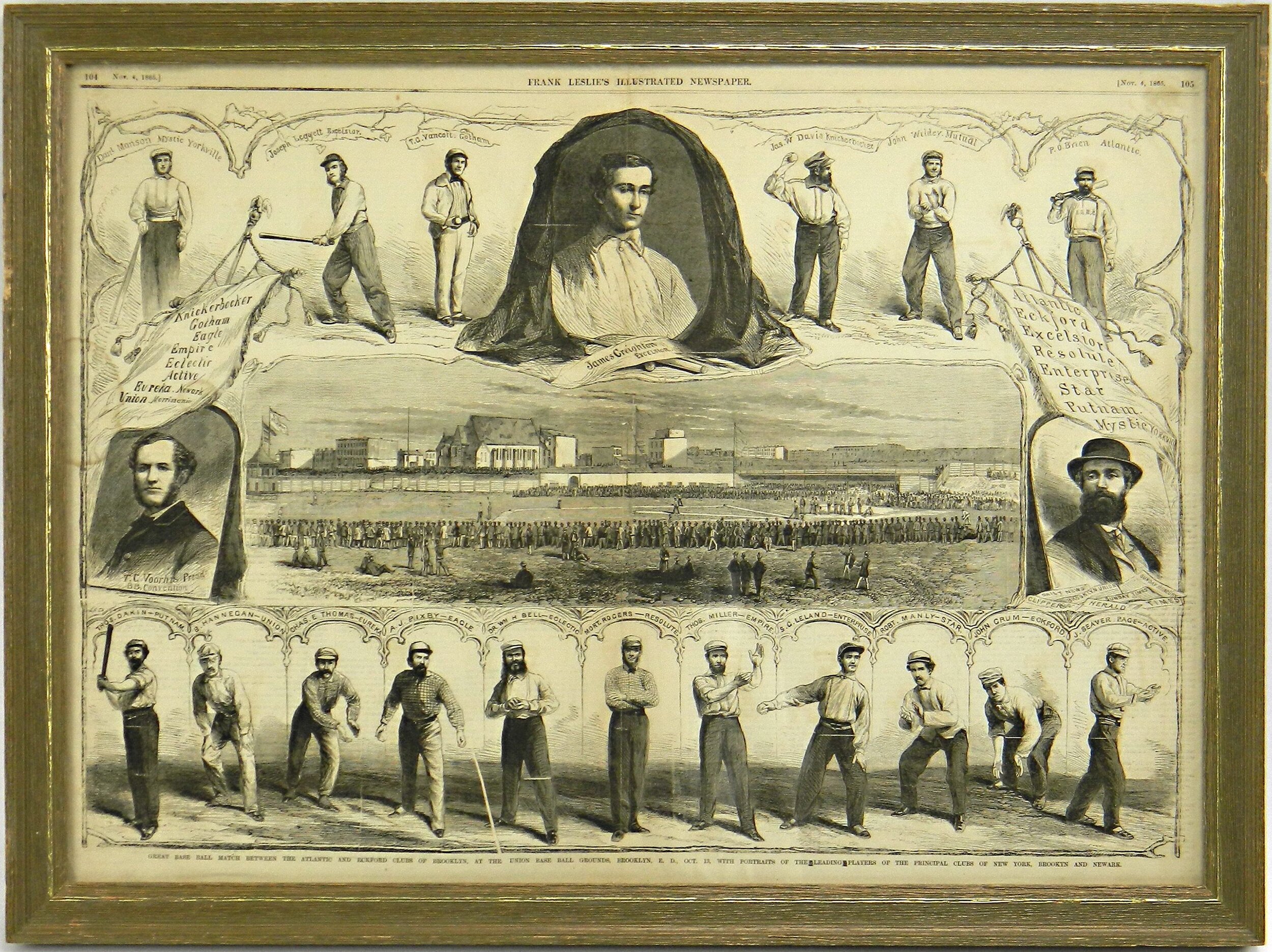

In pre-Civil War baseball, playing the position of catcher required a degree of physical courage that we can barely conceive of. Catchers had no face masks or other equipment. The only thing preventing a pitched ball from skipping away from the field, allowing runners to circle the bases, was the catcher’s unpadded and unprotected body. Game accounts of the 1850s rarely tell of a pitcher being taken out of a game; catchers, however, were often removed with head or hand injuries. When there were two strikes, an aggressive catcher would move up behind the batter and spread out his bare hands, risking a fractured nose or cheek bone in order to catch a foul tip. Joseph Leggett, star catcher of the Excelsiors of Brooklyn, was very good at this. In his 1868 baseball instructional Henry Chadwick referred to this technique as “taking balls sharp off the bat, a la Joe Leggett…”

Joseph Bowne Leggett was born in Saratoga County in upstate New York in 1828. The Leggetts were an old Quaker family whose ancestors had settled in Queens in the late 17th century. Leggett moved to Brooklyn as a young man and worked in the family wholesale grocery business with an uncle and several cousins. He was a volunteer fireman with the baseball-playing Pacific Engine Company #14 on Love Lane in Brooklyn Heights. Leggett, his cousin James K. Leggett and another relative, Isaac Leggett, all served terms as foreman. (James K. Leggett later became president of the Brooklyn Fire Department). In 1861, when the Excelsiors were inactive because of the Civil War, two of Joseph Leggett’s teammates, Henry Polhemus and George Flanley, played for the Pacific #14 baseball team. In 1867 the nearly 40-year-old Joseph Leggett married the 20-year-old Alice Marks; they had three children.

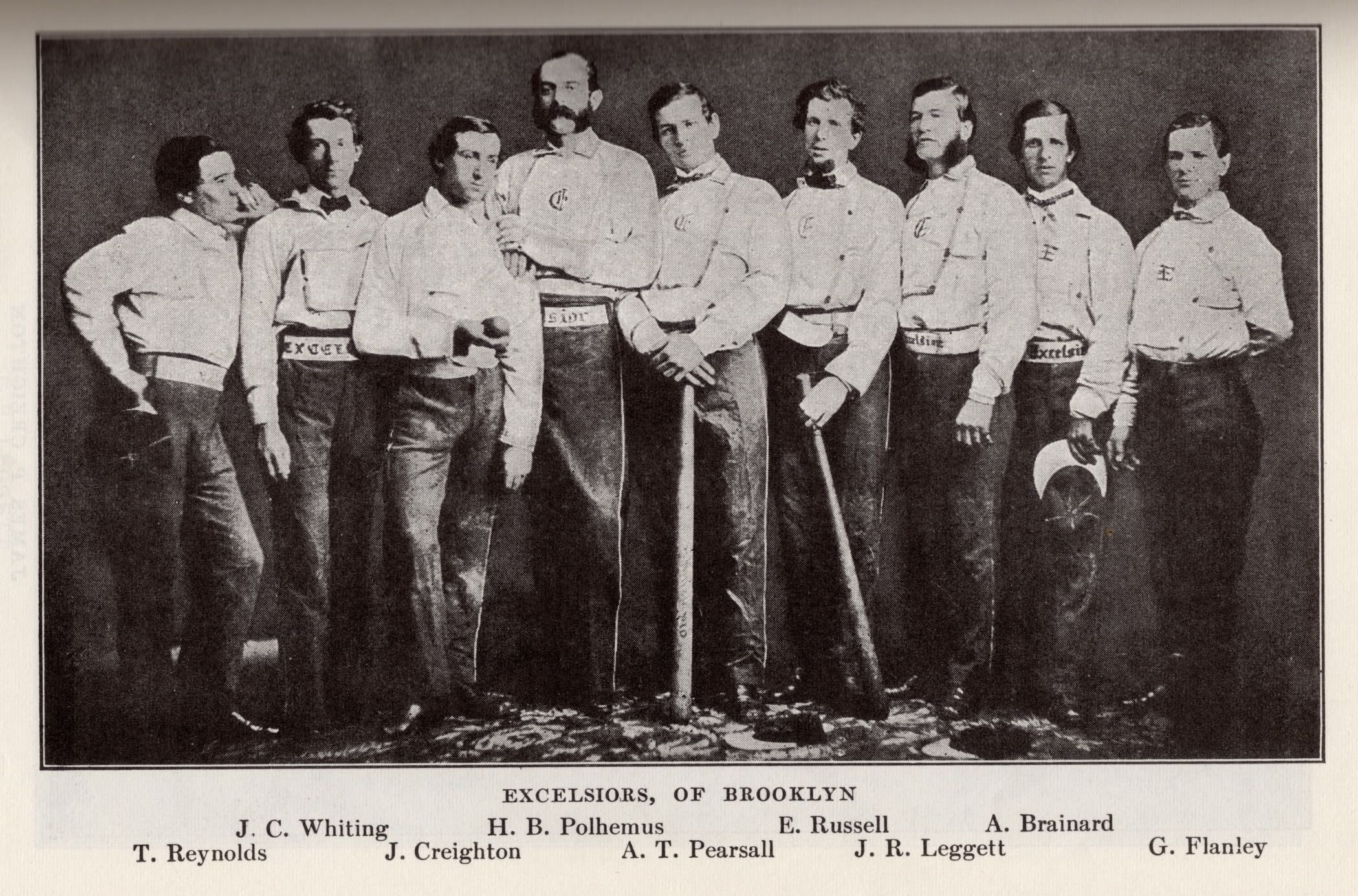

Leggett joined the Excelsiors in 1857 and was their best player until the arrival of pitching phenom James Creighton three years later. It is difficult to evaluate the batting statistics of Leggett’s day, but the Excelsiors kept a silver ball on which they engraved the name of their top batter for each season. In 1860 it was Joe Leggett. That was the year in which the Excelsiors made their famous road trips to eastern cities. One of their stops was Baltimore, where Leggett and Polhemus had earlier helped a business associate, grocer George Beam, found that city’s first baseball club, which was also called the Excelsiors. On July 22 the Brooklyn Excelsiors demolished the Baltimore Excelsiors, 51-6. Local fans were awed by the sight of Baltimore players swinging at Creighton fastballs after they were already in Leggett’s hands, and Leggett’s “daring, almost reckless” play behind the plate.

Leggett also acted as a combination pitching coach, trainer and talent scout for the Excelsiors. It makes sense that a catcher would serve this function, because pitchers of the time could only throw as hard and with as much movement as their gloveless catchers could handle. Leggett developed and trained not only the great James Creighton, whom he taught to lift weights, but also two of the other great pitchers of the day, Asa Brainard and Candy Cummings. In 1866 Leggett saw the teenage Cummings pitch and persuaded the boy’s parents to let him join the Excelsiors. Older than most of his teammates, Joe Leggett was looked upon as a father figure, who, in modern baseball terminology, policed the Excelsiors clubhouse. Well respected in baseball generally, he served as vice president of the National Association of Base Ball Players in 1862. The only wart on his baseball portrait was his odd hypersensitivity to crowds, a quality that contributed to the notorious forfeited championship game between the Excelsiors and Atlantics in 1860.

As fine a ballplayer and as solid a teammate as he may have been, Leggett was a deeply flawed human being. Both during and after his playing career, Leggett exploited his fame and the connections he made as an athlete to make a living. He held a string of jobs in institutions connected to the powerful men behind the Excelsiors. But he could not keep his hand out of the till. It may be that Leggett had a gambling problem. An underlying vice would help explain why Leggett’s transgressions so often met with sympathy and why his friends gave him one second chance after another. It is also possible, of course, that he was simply dishonest. In 1859 Leggett worked at the Brooklyn’s Mercantile Library Association, a favorite charity of the wealthy, where he was caught trying to rig an officers’ election. During the Civil War Leggett served as a quartermaster in the 13th New York State Militia under fellow Excelsior Colonel John Woodward. In 1869 Leggett was appointed treasurer of the Widows and Orphans Fund of the Brooklyn Fire Department. Three years later, he failed to deposit the nearly $3,000 proceeds from a charity ball into the fund. An official investigation later found that his boss, a fellow ex-firefighter from Engine Company #14, had dropped the matter despite Leggett having reneged on a promise to pay the money back. Forced to resign, Leggett found a clerical position with the Brooklyn Police Department Excise Bureau, which issued liquor licenses. In 1877 $1000 in license fees went missing; Leggett disappeared and was fired. On January 4, 1878, the Brooklyn Union Argus reported the following.

Joe Leggett, the runaway clerk of the Excise Bureau, is still wanted at Police Headquarters. His whereabouts is a mystery. In consequence of his sudden and improvident departure his wife was obligated a few days before New Year’s to give up her residence in Monroe Street, and she and her children are now boarding with friends…Leggett’s best friends are loud in their denunciation of his misconduct, and loud in their praise of his wife’s fortitude under crushing trial.

This time, Joseph Leggett legged it. As far as we know he left New York never to return, apparently living the rest of his life under a false name. Family genealogical records have it that he died near Galveston, Texas in 1894, by one account in prison. Leggett’s new name and location may have been an open secret in the New York baseball world. In 1889 Chadwick reminisced in print about the great amateur Excelsiors. “Ed Russell, Asa Brainard and Tom Reynolds are dead and gone,” he wrote, “Pearsall is a doctor in the South [sic: by then he had moved back home to upstate New York]…Harry Polhemus is one of Brooklyn’s society men and a millionaire; John Whiting is in business in this city, and his brother Charley also, I believe, while Joe Leggett is—well, I will be silent for old times’ sake.”*

*Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 15, 1889, p.4