The WASPiness of Early Baseball: Part I

Early baseball history is as white as a beach resort in Thailand. The main reason for this is that mid-19th-century journalism, which is historians’ primary source of information about contemporary culture and daily life, was aimed at a very narrow sliver of American society, the white, Protestant emerging urban bourgeoisie. Baseball’s marketing efforts were also aimed at this class, whose members had the money and leisure for adult athletics.

Baseball has always sold itself as quintessentially American. Today, we see baseball’s racial and ethnic diversity as a natural part of its Americanness. According to the ideology of the modern game, learning to play and watch baseball is an Americanizing experience that teaches our values. When the descendants of immigrants from a particular ethnic immigrant group appear in MLB uniforms, it is regarded as a sign that that group has made it and has become fully American. African Americans were almost universally excluded from baseball at the upper competitive levels from the beginning of the Amateur Era in the 1840s through the Professional Era until the middle of the 20th century. But that has not stopped Major League Baseball from casting itself as an agent of social change in its version of the Jackie Robinson story. The sport’s long history of racial exclusion cannot be denied or erased, even if MLB did set a moral example by peacefully and more or less voluntarily breaking its own color line in 1947.

What it means to be American has changed dramatically in the 175 years since baseball emerged as a national institution. It is a shock for a modern American to learn how homogeneous both early baseball and the America that created it were. This country was settled in the 17th and 18th centuries almost entirely by Protestant immigrants from Great Britain (England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland, including what we now call Northern Ireland). It had negligible amounts of immigration between 1790 and 1845. African Americans, of course, were already here. A paltry 60,000 or so immigrants arrived here per decade, as the country grew from a total population of 3,918,000 in 1790 to 17,018,000 in 1840. In 1790 more than two and a half million Americans, or about 66% of the total population, were of British ancestry. The rest had ancestors from Africa (20%) and Germany (7%); smaller percentages were descended from immigrants from the Netherlands, France and other countries. Because these groups were largely Protestant, Catholics made up only 1.6% of the US population in 1790. As late as 1830, less than 2% of the US population was foreign-born.

Despite the fact that most Americans were of British ancestry, the America of the first half of the 19th century was fiercely nativist in politics. It was hostile to Great Britain – America’s bitter enemy in two recent wars -- and fearful of foreign influence generally. Baseball reflected and embodied this prevailing nativism. India, Australia, Jamaica, South Africa and dozens of other former British colonies adopted the English sport of cricket and made it their own, but not the United States. We insisted on creating our own, homemade national sport.

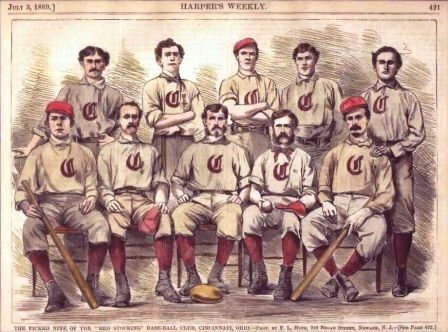

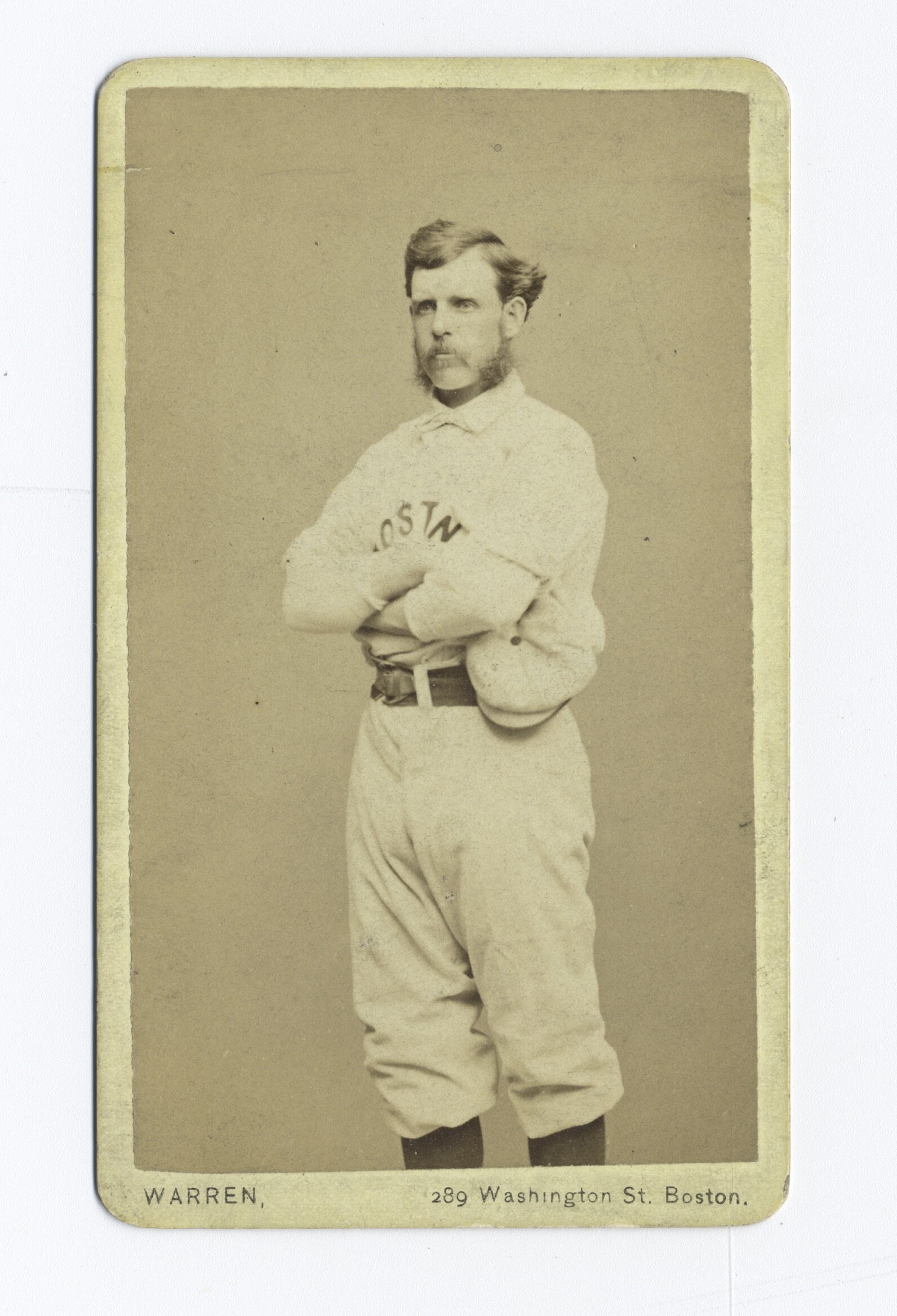

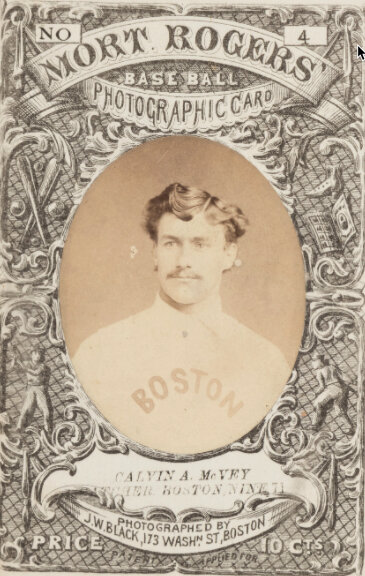

The first baseball players that we know anything about were amateur athletes who organized clubs like the Knickerbockers and Gothams in New York, Brooklyn and other cities in the 1840s and 1850s. At least 90% of them were native-born, white, Anglo-saxon and Protestant. Considered from the point of view of class, the members of the prominent Amateur Era baseball clubs belonged to an even narrower demographic, the forerunners of the modern middle class; very few were from high or low socio-economic backgrounds. Ironically, the earliest African-American baseball clubs that we know anything about had a similar class identity. The Pythians, an African American baseball club that was formed in Philadelphia the mid-1860s, was made up of doctors, lawyers, teachers and merchants – the kind of men who, if they had been born white, might have joined the Knickerbockers or the Gothams.

African Americans had played baseball and formed clubs before the Pythians, but the racism of the NABBP and that of the mainstream press kept the African American baseball scene in the shadows. We only know that it existed from scattered mentions in print and from the fact that competitive African American clubs like the Pythians emerged in the post-Civil War years. They could not have come from nowhere. Integrated baseball clubs may have been virtually unknown in the Amateur Era, but as the baseball movement expanded beyond the New York metropolitan area and went national, it crossed existing racial lines.

It is significant that Jews do not seem to have attracted the hatred of nativists -- or even their notice. In researching the lives of hundreds of baseball men from this period, I encountered several Jewish baseball players, but virtually no evidence of anti-Semitism in amateur baseball. This reflected the views of the emerging urban bourgeoisie of that time. New York City’s small Jewish community was long-established and thoroughly assimilated in all ways except for religion; New York’s first synagogue was founded by a group of Sephardic Jews who arrived in the 1640s, 145 years before that city’ built its first Catholic church. New York’s native-born Jews were so similar to and compatible with the Protestant mainstream that the religious identity of Jewish baseball players was hardly mentioned. This was in stark contrast to Catholics, who were feared and despised even before the arrival of hundreds of thousands of deparately poor Catholic refugees from Ireland and, to a lesser extent, Germany in the late 1840s and 1850s.

To be continued in Part II….