The Man Who Invented Modern Pitching - Which Killed Him

The story of James Creighton is the oldest and saddest one in the baseball book.

Creighton, who became baseball’s first national star in the early 1860s, possessed the game’s most indispensable skill, the ability to get good hitters out. The rare players who can do that have been overworked and abused for 150 years. Every time they take the mound, modern pitchers are doing what James Creighton was the first to do -- walk a tightrope between making effective pitches and injuring themselves. Sometimes they fall off the tightrope. Today, it hardly makes news when an exhausted, overworked pitcher literally rips his elbow ligament into shreds; surgeons simply put in a new ligament taken from another part of the pitcher’s body and he is back at work in 18 months. If that one tears, they do it again. Rest a sore shoulder? Not with games to win and money on the line. Arm injuries end careers in the majors, the minors, college and high school every day. But throwing a baseball too hard for too many innings cost Creighton much more than a career.

James Creighton was born in 1841 and died in 1862. That is no misprint — he died at 21. He played during baseball’s Amateur Era (the first professional baseball league was founded in 1871.) Before Creighton, baseball was a hitter’s dream. The rules of the time required that the rubber-packed, lively baseball be delivered dead underhand with no wrist snap. Think of pitching horseshoes rather than what we mean by the word pitching today. There was little speed or deception; pitchers more or less put the ball over the plate and ducked. There was no strike zone in Creighton’s day because none was needed; pitchers gained little by throwing pitches that batters wouldn’t swing at and batters gained little by taking hittable pitches. Not surprisingly, home plate took a beating. A score of 7-4 raised more eyebrows than a score of 65-50.

Around 1860, while pitching for the great Excelsiors of Brooklyn, Creighton figured out a legal or apparently legal way to throw very hard, with unusual movement and command. His new style of pitching was immediately and widely imitated. Transforming pitching into a weapon, it so upset the balance of power between offense and defense that it led to the creation of the strike zone, which has been the center of the action of a baseball game ever since. Before the strike zone, baseball games were decided by which defense did a better job of controlling balls put in play; ever since, they have been decided by who wins control of the imaginary box hovering over home plate. The strike zone is the main reason that baseball is watchable on TV.

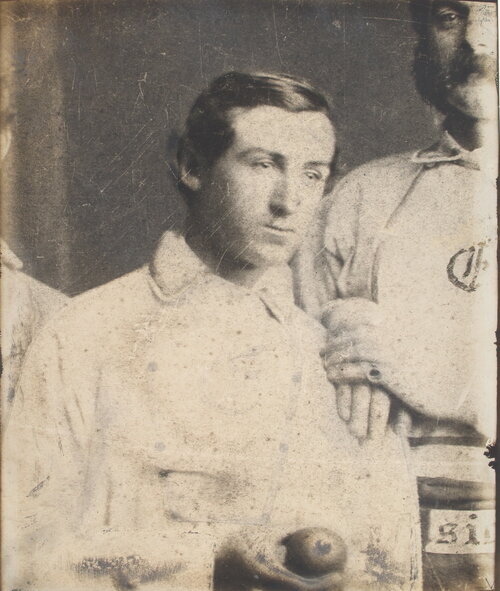

The first baseball card?

James Creighton’s legacy remains with us in other ways, too, whether most fans have heard of him or not. He was the subject of a posthumous carte de visite that may be considered the first baseball card. In August of 1858 James Whyte Davis of the Knickerbockers wrote parody song lyrics for a banquet attended by the principal New York and Brooklyn baseball clubs. This is one of the stanzas about the Excelsiors:

They have Leggett for a catcher, and who is always there,

A gentleman in every sense, whose play is always square;

Then Russell, Reynolds, Dayton, and also Johnny Holder,

And the infantile “phenomenon,” who’ll play when he gets older.

The “infantile phenomenon” is a veiled reference to the teenage James Creighton, then playing for one of the Excelsiors’ affiliated youth clubs. It comes from Charles Dickens’s 1838 novel Nicholas Nickleby, in which a theatrical child prodigy is advertised as the “infant phenomenon.” It is likely the source of the term “phenom,” which is still baseball slang for a promising young player.

In the absence of video or film, we don’t know what Creighton’s pitching actually looked like. Atlantics star Pete O’Brien, who batted against him, described it as “something entirely new, a low, swift delivery, the ball rising from the ground past the shoulder of the catcher.” Does this mean that Creighton delivered the ball from a lower angle than other pitchers, or that his pitches had a four-seam-type hop to them, or that he was throwing an underhand breaking pitch of some kind? Eyewitnesses all agreed that Creighton threw extremely hard, but they also talked of his use of “twist.” What they meant by that is unclear. It seems that Creighton was able to achieve a break or some other kind of deceptive movement on his pitches. He may have thrown the first curve ball.

Based on O’Brien’s description of Creighton’s delivery, some of Creighton’s perceived velocity may have been the result of a deceptive release point. Before radar guns, it was not easy to distinguish between pitches that were difficult to pick up visually and pitches that were simply traveling very fast. Contemporaries of Creighton also said that he did not run up to the pitching line, as other pitchers of the time did, but took a single stride like a modern pitcher. The few images we have of Creighton’s delivery show him twisting his lower body in a strange way. Both would be consistent with Creighton using a lot of hip torque, which would create a whipping action and increased arm speed. They are also consistent with throwing a curveball, which is difficult to do while on the run.

We may not know exactly what kind of pitches James Creighton threw or how he threw them, but we do know that they had a devastating effect. When overmatched batters realized that they couldn’t hit Creighton, they went to Plan B — they tried to tire him out by leaving the bat on their shoulders and taking dozens of pitches. This despised tactic caused the rules to be changed to give the umpire discretion to call strikes as a warning. It took a few years, but called strikes eventually became part of the game. This was followed by called balls and, ultimately, the establishment of the modern strike zone. The strike zone that we use today is essentially a response to the revolutionary new way of pitching pioneered by James Creighton.

During a game on October 14, 1862 Creighton became ill. He died in agony four days later. The press and public assumed that the cause was a traumatic injury sustained during the October baseball game. The September 16, 1865 Brooklyn Daily Eagle gives the following account: “...in making a third attempt at the ball [Creighton] struck with great force and immediately fell down. After a while he felt no more uneasiness, and played the balance of the game. But alas! He had ruptured some of the internal organs, and in a few days the baseball fraternity were startled with the announcement, ‘Creighton is dead.’” Like an expensive Bordeaux, the story of Creighton’s death improved with age. In his 1910 book The National Game, Alfred Spink published the following account by former Atlantics outfielder John C. Chapman: “I was present at the game between the Excelsiors and the Unions of Morrisania at which Jim Creighton injured himself. He did it in hitting out a home run. When he had crossed the rubber [i.e. home plate] he turned to George Flanley and said, ‘I must have snapped my belt’... It turned out that he had suffered a fatal injury.”

Neither of these stories can be true. They are inconsistent with Creighton’s known actual cause of death, a strangulated intestine. A strangulated intestine is normally caused by an inguinal hernia, which is an inherited weakness or gap in the inguinal canal, behind the groin area, through which contents of the abdomen sometimes protrude. If a section of intestine becomes caught, its blood supply can be cut off, which would lead to a gangrene infection. Today, an inguinal hernia can be easily diagnosed and repaired with surgery, and a strangulated intestine is quite treatable. But in the 1860s there were no surgical options or antibiotics, so reaching the gangrene stage meant certain death.

Dr. Joseph B. Jones, physician and President of the Excelsior baseball club of Brooklyn

There are two problems with the idea that Creighton fatally injured himself swinging a bat one day in 1862. One is that an inguinal hernia is a chronic condition and is not caused by a single event. The hernia would have worsened over a long period, probably years. Pitchers in Creighton’s time threw a lot of pitches in a game. Creighton threw more than most because of the waiting tactics used against him by overmatched batters. It was not unusual for Creighton to throw over 50 pitches in a single inning or to record game pitch counts in the 200s or even the 300s, numbers that are unthinkable today. His unusual pitching delivery may have added additional strain. The other problem is that the inguinal hernia was a well-understood medical problem in the mid-19th century. Creighton would have been treated for it, and would have worn a truss. And the Excelsiors club was full of doctors. At least two of them, team president Joseph B. Jones and first baseman A. T. Pearsall, knew Creighton intimately. They would have known that inguinal hernias are exacerbated by long-term physical stress, for instance from repeated violent twisting or weightlifting and they would have known of the risk of a strangulated intestine. It is hard to escape the conclusion that the people that Creighton played for and with knew that they were risking his health in order to win baseball games.

James Creighton’s breathtaking grave monument in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood cemetery

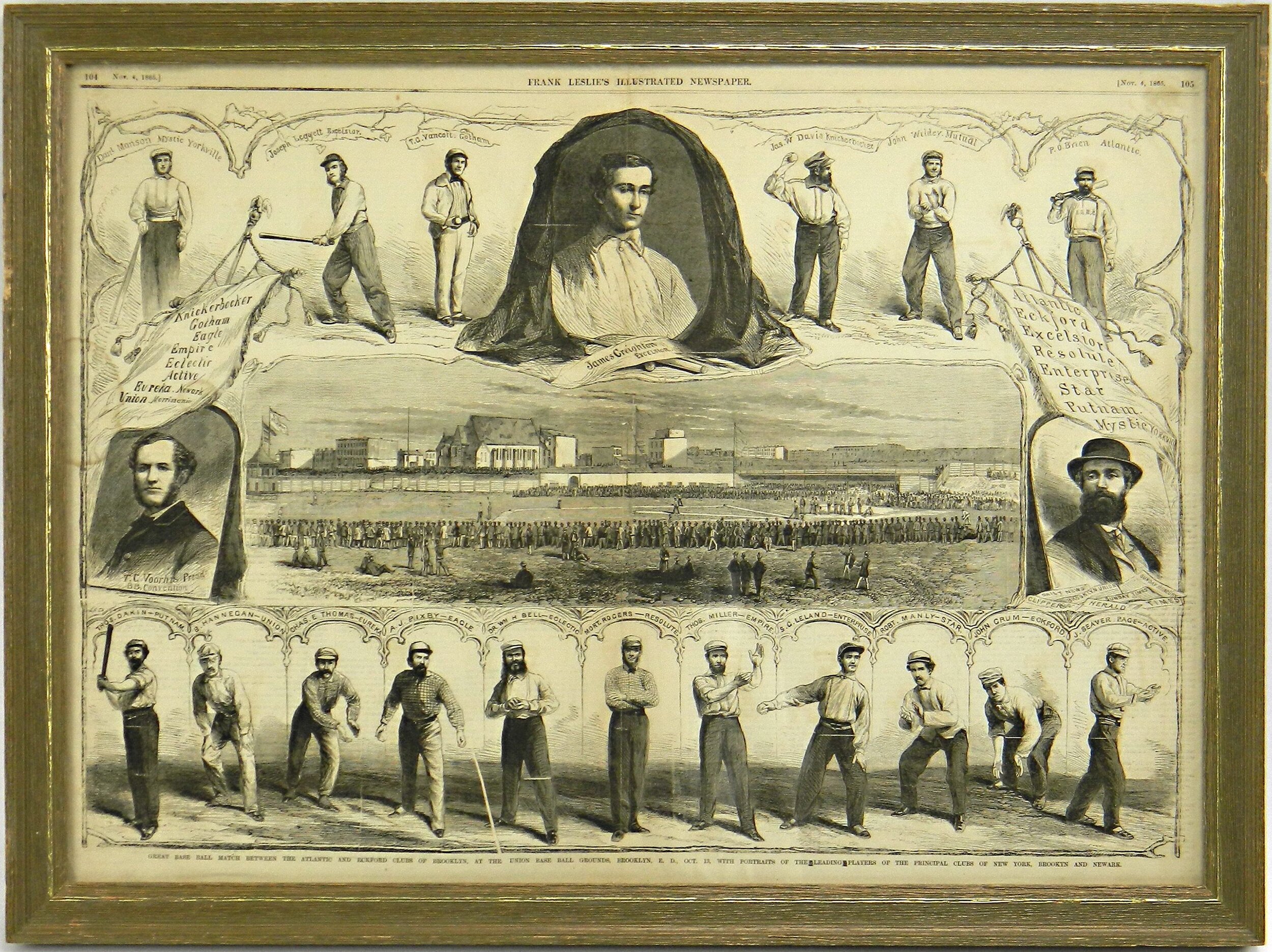

The loss of Creighton at twenty-one years old hung heavily over baseball for years. In 1865, three years after Creighton’s death, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper carried a two-page spread depicting the baseball world and its principal clubs and figures. At the top is a larger than life James Creighton, shrouded in black crepe, looking down as if from the next world. Creighton’s death cast a particular pall over the Excelsiors. Even though they continued to play through the 1860s, the club dropped quickly out of the ranks of the top clubs. Grief and guilt over Creighton’s untimely death may have played a role in this. Later baseball clubs made pilgrimages to Creighton’s grave monument in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood cemetery—a form of tribute that has no parallel. In 1866 the Washington Nationals traveled to Brooklyn to play the Excelsiors. They stopped at Green-Wood to pay their respects to Creighton. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle called Creighton’s grave “the Mecca of ball players, the sole relic of the noblest and manliest exponent that the national game has ever had.”