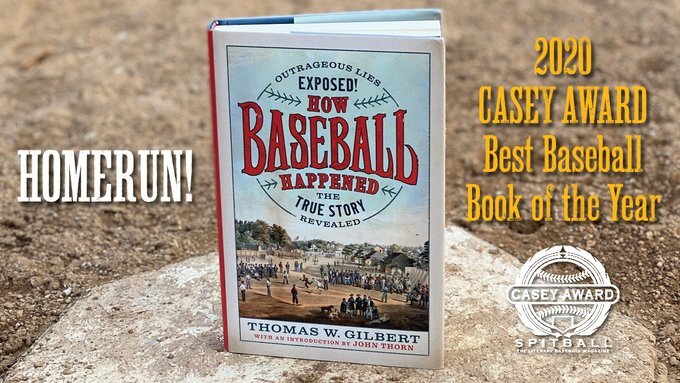

PAPERBACK IN STORES APRIL 5, 2022!

“A delightful look at a young nation creating a pastime that was love from the first crack of the bat” — Paul Dickson in the Wall Street Journal

"By far the best - brilliant, stimulating, funny. Does for baseball what David McCullough did for U.S. history: places baseball firmly in the mainstream of American culture." — Lorine Parks, Judge 2020 Casey Awards

SABR SEYMOUR MEDAL FINALIST!

“From the very first page of How Baseball Happened, the reader knows he is in for an exciting, often witty and amusing, ride through the game's earliest years.” — Mike Shannon, editor Spitball Magazine

“In a tone that’s courageous as it is concise, Gilbert does his research – again, stuff that’s been out there before that doesn’t seem to matter – and presents it in a scholarly approach that’s as enlightening as it is entertaining” — Tom Hoffarth

“…wonderfully researched and engagingly written, which is no small feat given the time period covered. But Gilbert gets the info and he presents it entertainingly, mythbusting baseball’s origin story in way that would make Adam Savage and Jamie Hyneman proud and providing compelling histories of a wealth of characters from baseball’s early days, individuals straight out of Horatio Alger stories.” — Chris Davies at letsgotribe.com

“How Baseball Happened is a brilliant new approach to our game and its author tells a hundred stories you haven’t heard before”

“…a story well worth telling, and Gilbert recounts it with humor, irony, passion, and a sharp eye for colorful detail.” — John Wilson in First Things

“In How Baseball Happened, Thomas W. Gilbert brilliantly gathers hidden treasure long buried in newspaper accounts and diaries to present a rich and nuanced picture of American baseball as it grew and blossomed. Along the way, he explodes myths that have long shaped our understanding of this great game. This is a tart and funny trip through the raucous and aspiring culture that shaped baseball, with its volunteer firefighters, urban professionals, bloodstained butchers, and brawling gamblers.”

―Edward Achorn, author of Every Drop of Blood, The Summer of Beer and Whiskey, and Fifty-nine in ’84.

Look for it at your local bookstore!

The wrongness of baseball history can be staggering.

You have heard that Abner Doubleday or Alexander Cartwright invented baseball. Neither did.

You have been told that a club called the Knickerbockers played the first baseball game in 1846. They didn’t.

You have read that baseball’s color line was uncrossed and unchallenged until Jackie Robinson in 1947. Nope.

You have been told that the clean, corporate 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings were baseball’s first professional club. Not true. They weren’t the first professionals; they weren’t all that clean, either.

You may have heard Cooperstown, Hoboken, or New York City called the birthplace of baseball, but not Brooklyn. Yet Brooklyn was the home of baseball’s first fans, the first ballpark, the first statistics, and the man who invented modern pitching.

Most of these untruths are not mistakes; they are lies designed to market the sport.

How Baseball Happened tells the real story of where our first sport came from and how it conquered a nation. Baseball’s true founders were the thousands of amateurs—ordinary people—who played without gloves, facemasks, or performance incentives in the middle decades of the 19th century. Unlike today’s pro athletes, they lived full lives outside of sports. They practiced professions, built businesses, and fought in the Civil War.

Baseball was originally supposed to be played, not watched. This changed when crowds began to show up at games in Brooklyn in the late 1850s. We fans weren’t invited to the party; we crashed it. Professionalism wasn’t part of the plan either, but when an 1858 Brooklyn versus New York City series accidentally proved that people would pay to see baseball, the writing was on the outfield wall.

When the first professional league was formed in 1871, baseball was already a fully formed modern sport with championships, media coverage, and famous stars. Professional baseball invented itself, but not the sport of baseball. Baseball’s amazing amateurs had already done that.

What really happened is not only truer than the lies and the marketing, it’s also a better story.

More from the book:

Baseball’s original origin story is the Knickerbocker story, which goes like this.

In 1845, a group of amateur athletes from New York City formed the first baseball club and published the first baseball rules. In some versions of the story, bank clerk Alexander Cartwright was the driving force behind both. All of the Knickerbockers were white men; almost all of them were native-born Protestants. Among other rules innovations, the club was the first to outlaw the practice of “soaking,” which meant smacking baserunners with a thrown ball in order to put them out. This was an important step forward in baseball’s evolution from a children’s pastime because adults preferred a game from which they did not have to limp home. Running out of playing space in New York City, the Knickerbockers wandered in the wilderness until in 1845 they found a home on the Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey, fifteen minutes by ferry from lower Manhattan. The Knickerbockers were influential gentlemen who popularized the game. Up sprang the Eagles, Gothams and Empires. These were followed by many more imitators in Brooklyn, New Jersey and the greater New York metropolitan area. The first players were dilettantes who put more effort into post-game banquets than into vulgar pursuits like recruiting, training or trying to win. The Knickerbockers ruled over baseball until, to their dismay, the game spread downward to the unwashed working classes. As it spread outward to Boston, Philadelphia and the rest of the country, the Knickerbockers lost control over the sport that they had made, opening a Pandora’s box of professionalism, gambling and corruption.

Two parts of this story are true. Almost all of the Knickerbockers were white American-born Protestants and the Barclay Street ferry did get you to Hoboken in fifteen minutes.

Suburbs like Morrisania — then Westchester County, now the South Bronx — were a new idea in the 1840s and 1850s; they promised well-off New Yorkers fleeing dirty and disorderly downtown Manhattan the best of both worlds, urban and rural.

A feature of city life that suburbanizing New Yorkers took with them was baseball. Yorkville, Harlem and all of the other early New York City suburbs had baseball clubs. The plan for Morrisania included playing grounds for the Union baseball club near 163rd Street, within walking distance of the Melrose station on the New York and Harlem Railroad line. In the 1860s the Unions built an enclosed ballpark with facilities for spectators, at the present location of Crotona Park in the Bronx. Crotona Park still has diamonds and a lively baseball scene. Hall of Fame slugger Hank Greenberg played there as a teenager in the 1920s; Manny Ramirez played summer ball there in 1990, as my son did in the 2000s.

The New York Knickerbockers have gone down in baseball history as gentlemanly aristocrats. But they weren’t. Most members of the club were economically comfortable merchants, entrepreneurs, insurance men, bankers, lawyers and doctors — what we today would call upper middle class; no more than one or two could be classified as old money rich.

Exaggerating their social status was not necessary for the original purpose of the Knickerbockers origin story—to promote amateur baseball to the respectable urban bourgeoisie. It was professional baseball, long after the fact, that converted the Knickerbockers from would-be gentlemen into the real thing. As baseball’s Amateur Era faded from memory, the real Knickerbockers were replaced by caricatures. In 1911 Albert Spalding, major league baseball’s most powerful owner and the man who bought and paid for the Abner Doubleday story, wrote the first attempt at a full history of baseball, America’s National Game. The book’s first printing of 5,000 copies sold out in 60 days; it sold 90,000 more in six months. In the chapter on the Knickerbockers, Spalding converts socially ambitious urban white-collar workers interested in physical fitness into upper-class twits in anachronistic knickers and tri-corner hats. “In 1842,” he writes, “a number of New York gentlemen—and I use the term ‘gentlemen’ in its highest social significance—were accustomed to meet regularly for baseball practice games. It does not appear that any of these were world-beaters in the realm of athletic sports…. Let us not forget that the men who first gave impetus to our national sport…were gentlemen ‘to the manor born,’ men of high tastes, of high ability, of upright character.” Baseball historians stopped writing this kind of bullshit decades ago, but the effects of Spalding’s book on baseball’s historical narrative are not easily undone. The first step in understanding how baseball really happened is understanding that this is a lie; the second step is understanding who told the lie and why.