Who gave us baseball? There are many answers to this question, but here is one that you probably have not heard before: epidemic disease.

I spent most of the past several years doing research for a book on baseball’s beginnings, which meant reading a lot of newspapers from the 1830s, 40s and 50s. The America I encountered there was a strange and unfamiliar country, particularly when it comes to sports. Today we are world famous as the sports-mad nation where the four seasons of the year are baseball, football, basketball, and ice hockey—where ordinary people run and work out into their 40s and 50s; where old age and golf are inseparable; and where someone coined the word “athleisure.”

Believe it or not, Americans were once known for the exact opposite. Before the late 1850s we had no sports leagues. Newspapers did not have sports sections. Hard-working rural grownups had no time for games. Male city-dwellers had leisure, but they spent it drinking, smoking, chewing and gambling; they were allergic to exercise and went outdoors when they needed somewhere to spit. The only widely popular adult team sport was cricket, but cricket was played mostly by immigrants from Great Britain. Boxing and horseracing were popular, but Americans participated in those by betting on them.

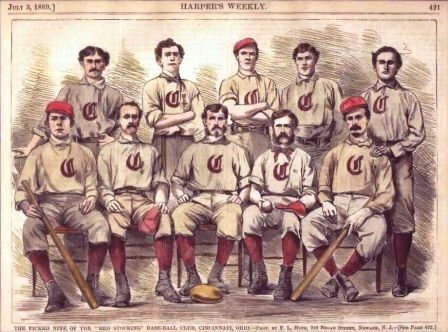

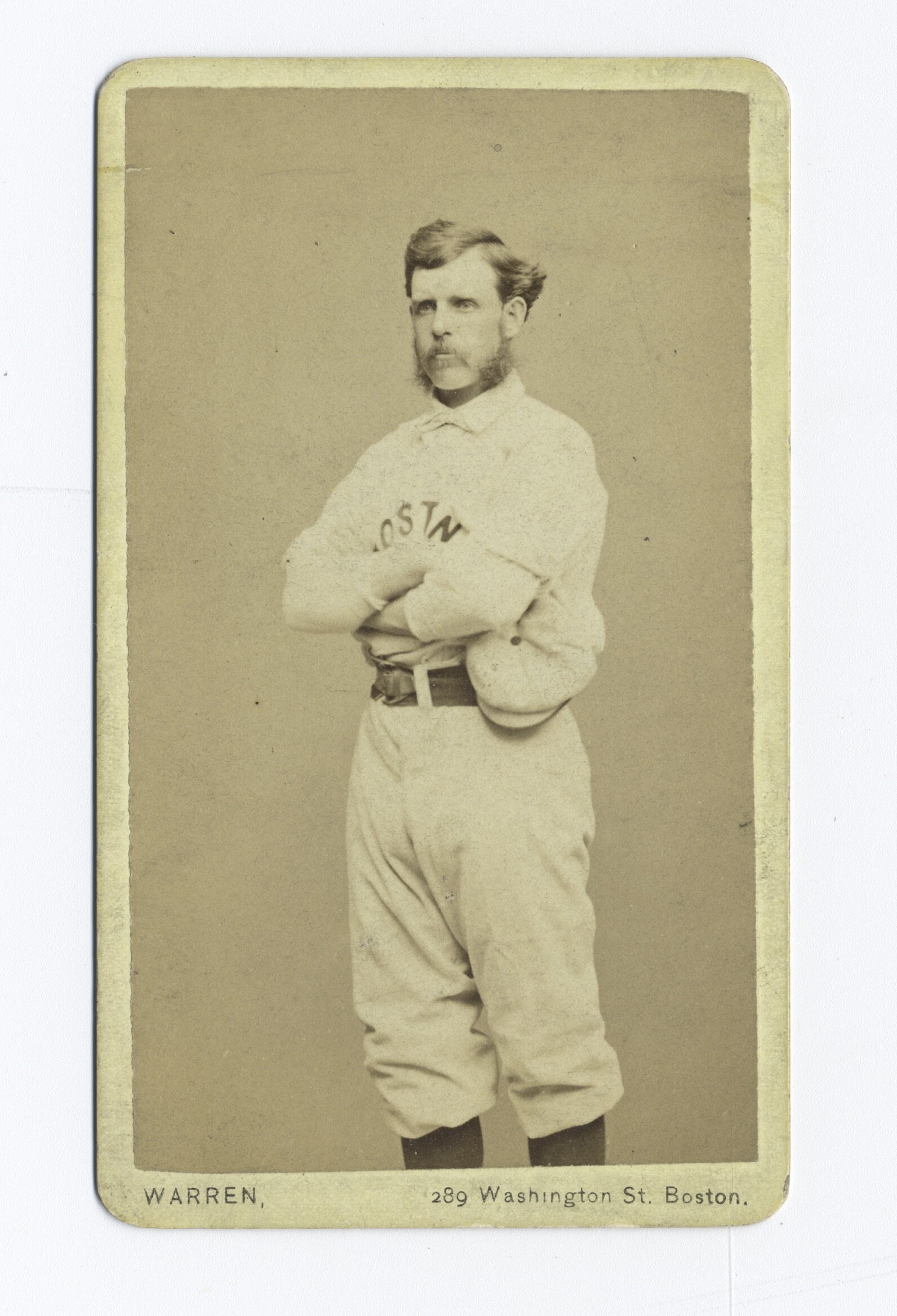

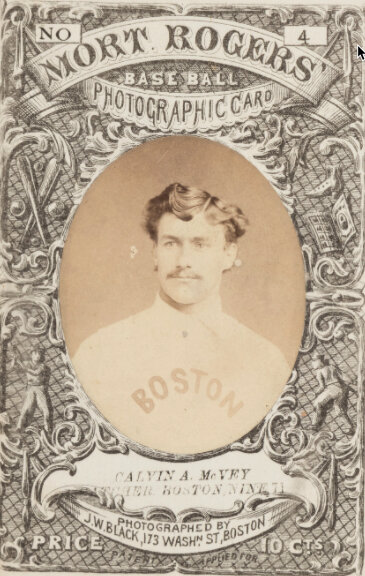

Then baseball happened. Long played in New York City as a folk game, mostly by children, baseball began to catch on as an adult sport in the 1850s, first as recreation, second as entertainment. Baseball went national with astonishing speed. By the late 1860s, it was being played and watched from coast to coast. Baseball the sport was completely and gloriously new. It was American-made. It was not primarily about betting. And it was not yet a business; the first professional baseball league, the National Association, did not turn its first stile until 1871.

What inspired our pudgy, dyspeptic forefathers to leave the office early on a sunny day, roll up their sleeves and take up the sphere and ash? The answer is there to be found in those pre-Civil War newspapers. They are full of articles, editorials and ads urging American adults to exercise. Baseball was adopted and advocated by a broad-based sports movement that began in New York and other East Coast cities in the late 1850s. Journalists like Walt Whitman were early and enthusiastic converts. One of the movement’s principal goals was patriotic: to bring together a fragmented nation in the same way that cricket united the United Kingdom. The other was to improve America’s health. Among the leaders of the baseball movement were reforming physicians who believed that fresh air, exercise and sunlight could offer protection from yellow fever, typhoid, cholera and other mass killers that attacked 19th century America in terrifying waves.

This is another aspect of daily life in 19th century America that I struggled to understand — death at the hands of epidemic disease. This was a death that came not as a rare misfortune, and not, as in most of my lifetime and in the lifetimes of my parents and my grandparents, a death that made a kind of sense, like the death of the very old, the chronically ill, or casualties of war or violent crime. Epidemics came out of nowhere to kill indiscriminately, without reason or explanation. They took away thousands of lives. They also took away survivors’ sense of safety and their expectation of a life span of 60 or 70 good years. In the spring of 2020, this kind of death and the fear that it brings is easier to understand.

Cities took the brunt of 19th century epidemic disease. Cholera killed roughly 3,500 New Yorkers in 1832, 5,000 in 1849 and 2,000 in 1854 – a far higher percentage of the city’s population than the Covid-19 numbers, at least so far. Wealth and privilege did not confer immunity. The 1849 outbreak killed former President James K. Polk. Like a sport, epidemic disease had a season. In July and August, the comfortable classes got out of town. Downtown areas fell silent. Mainstream medicine had no answers. Conventional medical theory held that cholera and other diseases were caused by vapors given off by decomposing organic matter, sudden changes in temperature, or eating unripe fruit. Conventional medical theory was wrong. With little scientific understanding of how infectious diseases work, doctors and public health officials had nothing to fight them with but offices and titles. Americans lived with the terrible possibility that the next epidemic might suddenly steal their lives or their loved ones.

Sports offered hope. In 1852 a man named Joseph Jones, who had recently opened Brooklyn’s only gymnasium, placed an ad in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. “Our people,” it reads, “do not seem to understand the importance of …exercises, and they are therefore rather neglected. Whoever takes them regularly may bid defiance to consumption [tuberculosis] and all its handmaids. They develop the chest and limbs, give firmness to the muscle, and send a glow of ruddy health over the cheek. Sedentary men, go and try them!” Jones eventually gave up on gymnastics, got a medical degree and joined the baseball movement. After playing with the Esculapians, a baseball club made up entirely of physicians, Dr. Jones joined the Brooklyn Excelsiors. Elected president of the club in 1857, he recruited young athletes and built the Excelsiors into one of the top clubs in the country. He then took them on baseball’s first road trip in order to promote what was then called the New York game to the rest of the country.

Daniel “Doc” Adams was the most important early member of the New York Knickerbocker baseball club; he was also a leading public health reformer. Adams and several other medical Knickerbockers helped create a city-wide dispensary system, supported entirely by private charity, that treated the poor and collected public health data. Adams and his allies campaigned for vaccination, better sanitation and physical education. The forgotten dispensary system is the direct ancestor of modern municipal hospital systems and health departments. During the cholera epidemic of 1866, newspaperman William Cauldwell, cofounder of the Union baseball club of then-suburban Morrisania (now the South Bronx) and a national baseball figure, published an editorial arguing that playing baseball could help fight cholera. “The vitality and strength derived from the inhalation of the pure oxygen of the atmosphere of a ball-field,” he wrote, “and the vigor imparted by open-air exercise, in which every muscle of the body is brought into play, are all conducive to a high degree of health, and of course prove strong obstacles to the approach of disease, especially of those of epidemic form, like cholera, which finds its first victims among those enervated by the lack of those very promoters of health.”

We now know that Cauldwell was wrong -- cholera is caused by drinking water contaminated with bacteria -- but the hope offered by the 19th century baseball movement was partly real. Physical fitness is not a cure-all for epidemic disease, but it strengthens the body’s immune system and the lack of it clearly makes us more vulnerable. We are told the same thing by today’s experts about Covid-19, an epidemic disease that has been particularly deadly for those who suffer from obesity and other, hidden chronic health issues. Yet in New York City, where I live, and in other cities, team sports have been canceled. I understand why I cannot watch the Yankees, but why can’t I play softball in the park? How ironic is it that Covid-19 has taken away baseball – a sport that was invented in a time of epidemic disease to give us unity, hope and health?

We could use a lot more of all three.